Going beyond watchlists

The role of OSINT in managing sanctions risk

Recent events in Ukraine have brought about the imposition of a host of additional sanctions on entities tied to the Russian state and those deemed to be in close proximity to President Putin. Gauging sanctions exposure has therefore become an immediate priority for the compliance and anti-financial crime community.

Although there are a number of commercial tools available to screen customers, suppliers and other relevant parties against sanctions lists, a more robust intelligence-led approach to detecting and reporting potential sanctions exposure is a necessity at times of heightened risk and active sanctions listings.

The limitations of traditional sanctions screening

Sanctions screening primarily relies on clients and third parties being screened against ‘watchlists’ – drawn from official sources (e.g., OFAC in the US, OSFI in the UK, the UNSC etc) – that provide details of the individuals and organisations that are subject to sanctions (herein as ‘designated entities’).

The efficacy of this process – presuming firms have accurate CDD files and information on suppliers and critical third parties – relies on watchlist providers curating the most up-to-date lists of sanctioned entities. It is also dependent on the accuracy and timeliness of the information provided by the different sanctions issuing authorities regarding the designated entities.

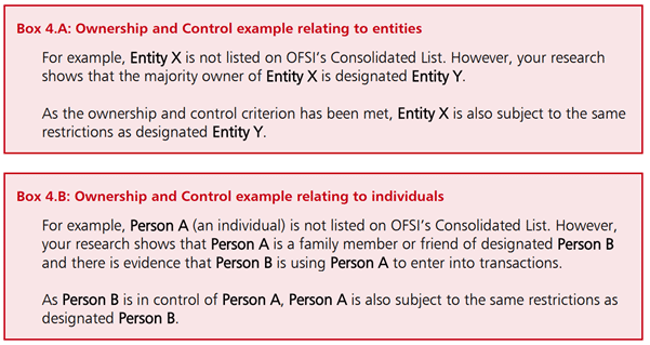

There is the further complication of ensuring that customers and suppliers are also screened against entities sanctioned by extension/association (ESE/As). Guidance provided by the UK’s Office for Financial Sanctions Implementation describes which entities should be deemed ESE/As. For example, an entity is considered to be owned or controlled directly or indirectly by another person that “holds (directly or indirectly) more than 50% of the shares or voting rights in an entity”, or “has the right (directly or indirectly) to appoint or remove a majority of the board of directors of the entity”. It also includes individuals that are “able to ensure the affairs of the entity are conducted in accordance with the person’s wishes”.

Ownership and control examples provided in UK sanctions guidance

A core challenge associated with identifying ESE/As is that ownership and control can be difficult to prove, especially in regimes where the use of cut-outs, proxies and intermediaries is commonplace. Further, firms will have their own ideas of what constitutes an ESE/A, which will be dependent upon their own risk tolerances. For example, Designated Entity A may own 48% of Company B; even though Company B does not meet the formal threshold of control, one might still include them on a list of ESE/As dependent on risk appetite.

Even with some customer screening vendors working hard to maintain accurate and comprehensive lists of designated entities and ESE/As there are reasons to go beyond these curated watchlists during this current crisis.

- Russia has been preparing for these sanctions for some time and will have started to implement measures to make life difficult for those looking to design, enforce, and comply with new sanctions measures. For example, in April 2019, Russia passed Government Decree 400 exempting certain companies affected by foreign sanctions to publicly disclose information on their executives, shareholders, subsidiaries, and affiliates. This makes reliance on official corporate records sources potentially problematic.

- In preparation for fresh sanctions, secrecy jurisdictions, and networks of proxy ownership/control will have been used to obfuscated true ownership and control structures.

- Risk and compliance solutions vendors face conflicting pressures on expanding ESE/A lists, especially where there are risks of potential legal action from those who might be named.

Taking a proactive, intelligence-led approach

The answer therefore is to adopt an approach where a range of additional sources are utilised in order to produce a more accurate and comprehensive list, and an organic understanding of designated entities, ESE/As and their wider networks. This process might look something like:

- Review the official lists of designated entities and comprehensively collate all relevant data related to the entity. The level of detail provided can vary greatly between different issuing bodies – but can include aliases, connected addresses, dates of birth, known associates etc;

- Use corporate records filings and other sources of corporate data, such as incorporation documents, annual reports and tax filings, to identify and map out formal corporate ownership structures;

- Use other publicly available data sources such as information from media searches, leaks data, social media, and the dark web, in conjunction with network visualisation and analysis tools, to identify individuals and entities with hidden controlling roles and ownership stakes (e.g. those held by family members, friends and known associates);

- Use website and domain analysis tools to identify whether sanctioned entities are operating via fronts that have not been officially declared;

- Use graph databases and network analytics tools to build a network view of this material that can be used for ongoing investigations; and

- Cross reference this data against customer and supplier databases to identify potential unknown risks. The issuing of new sanctions acts as a trigger event to run a comprehensive KYC/CDD review where the networks of entities and associates connected with high-risk customers are also comprehensively mapped, according to a risk-based approach, and then the overlap between these two datasets are analysed to identify hidden risks.

Leverage tools and tech

To be truly proactive about sanctions risk exposure, the use of graph databases and network visualisation tools is invaluable. A network view of risk will reveal things that are hard to identify from lists alone – such as potential non-official links to businesses and individuals who might act as cut outs and intermediaries in the process of sanctions evasion. Even if they are not designated, it is still worth considering whether the business wants to be facilitating them – a matter of financial crime compliance risk management vs financial crime risk management, or technical compliance vs effectiveness.

Further, core to making this proactive and intelligence-led approach more efficient and effective is the use of technologies that automate the mundane and time-consuming elements of this process, such as the collection of data from disparate data sources, the mapping and visualisation of networks, the cross referencing of data to identify connections, and the sourcing of information to demonstrate how and why decisions were made at each step of the process. Automating these activities frees up analysts to focus on more valuable activities such as directing investigations, making decisions, producing reports tailored to the needs of different sets of stakeholders, and sharing lessons learned with relevant parties to ensure the process is continually improved.

While this approach might seem like a step change in the way sanctions risk has been traditionally investigated and managed, taking a more robust approach does provide a range of benefits. Firstly, it will create a living archive of data that be added to and utilised on an ongoing basis. Having that body of data to refer to later will not only help to identify risk faster, but will allow the absence of risk to be identified faster and with the confidence that a robust methodology has been applied. Finally, to coin a phrase, financial crimes of a feather flock together – and so if sanctions-related risk is identified, there’s a strong chance other kinds of risks, such as money laundering and illicit trade, won’t be far away.