Reframing Wildlife Crime: International Networks and Organised Gangs

When most people think of wildlife crime, they might see it as being a relatively isolated affair. It’s easy to imagine individual poachers – or small groups at most – killing individual animals to make a profit; a distressing image, but ultimately a crime whose only victims are animals.

In reality, though, wildlife crime is now estimated to be the fourth largest illicit transnational activity in the world.1 It’s facilitated by huge transnational crime syndicates – often the same gangs behind human, drugs or weapons trafficking. Just like these crimes, it generates huge profits which are then laundered, meaning it also contributes to financial crime on a global scale.

So why is wildlife crime generally perceived to be less serious than other forms of transnational organised crime, despite the fact that it supports and is supported by them? Are we ignoring its true costs?

In this article, we’ll challenge the common perception that wildlife crime is an isolated issue. We’ll explore the true cost of these crimes, examine who’s involved and what can be done to stop them.

The cost of wildlife crime

The consequences of wildlife crime are very serious, even before we take into account its links to other types of transnational crime. Wildlife crime, particularly trafficking, is a key driver of species decline globally. According to current estimates, 10,000 elephants are lost a year to these crimes. To fully grasp the impact of this figure, the elephant population in Tanzania was estimated to be 135,853 in 2006. In less than 10 years, this number had declined to 50,433.2

The loss of species means that there is a loss in biodiversity, leading to less stable ecosystems – which has major consequences for our planet. Despite the typical image that many have of wildlife crime, it’s not just Africa’s species that are affected, either. Glass eels are poached from Europe and Asia’s pangolins are increasing victims of wildlife crime. Additionally, as we’ll explore below, there has been an increase in cartel activity within wildlife crime, meaning that American species are being targeted too.

The human cost

On top of the ecological cost of wildlife crime, it has immediate consequences for human communities. Those living close to common poaching sites experience violence as part of their daily lives, with 10-15 rangers killed each month.3 In cases such as the illegal bushmeat trade, communities who previously hunted bushmeat sustainably now suffer a loss of resources and future revenue.

Additionally, on an international level, the human cost of wildlife crimes is potentially dire. Within the illegal wildlife trade, humans come into much closer contact with certain species much more frequently then they otherwise would. This creates a major disease risk, as an infectious disease can jump from these animals into the humans handling them.

Wildlife crime as transnational organised crime

Even without considering its similarities to and connections with other forms of transnational organised crime, it’s clear that wildlife crime needs to be taken seriously. However, in order to understand the wider implications of wildlife crime and how it can be countered, it’s important to look at the bigger picture. In this section, we’ll look at how wildlife crime networks operate and where they intersect with other serious crimes.

Organised wildlife crime networks

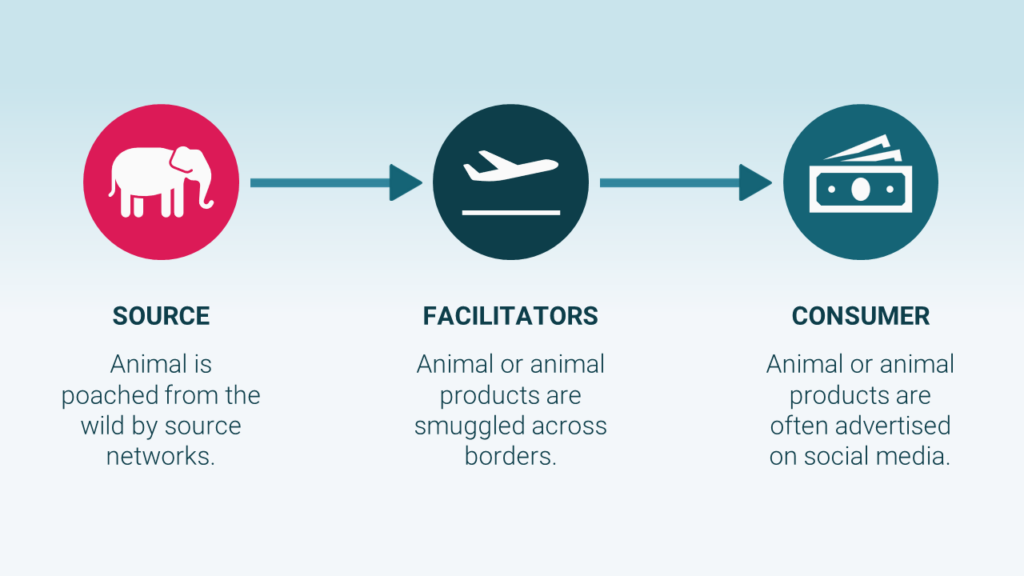

The complex organised networks behind wildlife crime resemble that behind other forms of serious transnational crime, such as human trafficking. Wildlife crime takes many forms – for example, wildlife trafficking can occur with live animals traded as pets, or with animal products such as rhino horn. However, the networks that facilitate the illegal wildlife trade are similar, regardless of the product traded. To understand how they work, we’ve outlined the key players below:

- Source: Poaching groups work to poach the animal from the wild. This could mean killing the animal to harvest valuable goods, or forcibly removing a live animal from its habitat. Even in the latter case, other animals are often killed to facilitate the process.

- Facilitators: Poaching groups sell their products to middlemen, who transport them across borders – eventually to the consumer country. This might take the form of smuggling, or operate under a veil of legitimacy. Particularly for trafficking live animals, fake export documents and permits can be created in order to transport the animal in plain sight.

- Consumers: Products are advertised and sold on social media and ecommerce sites.

It’s worth noting that the internet plays a major part at all levels of the supply chain. The ease of communication it allows means that the criminals within these networks can communicate with each other more easily. Poachers can advertise to middlemen, and middlemen can reach out to poachers; consumers can approach their brokers just as easily as those brokers can notify them of supply.

It’s not an isolated offence

Another commonality between each stage of the supply chain is bribery and corruption. As with other forms of organised crime, these are major players in facilitating this trade to continue. For example, in the illegal wildlife trade, a middleman responsible for transporting products might bribe state officials in order to obtain a permit claiming their goods have been obtained legally, meaning they will encounter less opposition at borders.

Bribery and corruption aren’t the only other crimes that surround the illegal wildlife trade.4 Aside from the violent crimes that surround the communities near poaching sites, wildlife crime also has direct links to other forms of serious organised crime. Often, the same networks behind wildlife trafficking have links to, and even directly practice, other forms of trafficking. For example, the high-profile wildlife criminal Vixay Keosavang was known to be involved with human trafficking networks.

Furthermore, in recent years American drug cartels have become increasingly involved in wildlife crime. Initially, cartels began trading for precursor chemicals to make drugs with the organised crime syndicates behind wildlife crime. However, they soon realised the huge revenues wildlife crime offers – as well as the fact that it’s often taken less seriously and therefore is considered a ‘less risky’ crime. Now, cartels dominate marine trafficking in Mexico and their influence on illegal wildlife crime is likely to continue growing further.5

Following the money

The profits that motivated cartels to operate within the illegal wildlife trade reveal another key aspect when it comes to understanding wildlife crime. Just like other forms of serious transnational crime, wildlife crime creates profits that need to be laundered. This means that wildlife trafficking can be considered a predicate offence for money laundering. It also means that, in order to counter wildlife crime effectively, a financial approach must be considered.

To put the profits from these crimes in perspective, it is estimated that the illegal wildlife trade generates $20 billion in criminal profits each year. This makes it the fourth most profitable crime globally,6 and highlights how crucial it is to ensure anti-financial crime responses are in place.

Wildlife criminals operate for profit, and they can only see the benefits of these profits by legitimising them. It’s not a question of whether these criminals will choose to launder their funds, but when and how. This presents a major opportunity to catch the criminals at this stage of their operations.

Common typologies and techniques

As with any other form of crime, increasing understanding of the common ways funds are laundered will help an anti-financial crime approach become more effective. A recent FINTRAC report analysed a sample of Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) related to the illegal wildlife trade. They found that the most common transactions were cash, wire transfers and email money transfers, and that several money laundering methods were used, including use of nominee, front companies and funds layered between related accounts. Additionally, these financial reports revealed further links between the illegal wildlife trade and other criminal activities, such as drug trafficking and fraud.7

Clearly, an effective financial crime approach to countering the wildlife trade would not only stop wildlife criminals directly, but help reveal the larger networks that facilitate this trade as well as other forms of serious organised crime. This doesn’t just apply when funds are laundered, either. For example, if someone is arrested at a border for smuggling illegal animal products, a financial crime approach allows us to begin unveiling wider networks. By tracing the source of the apprehended individual’s funds, we can see who else is involved rather than just disrupting this one stage of the supply chain.

What can be done to counter wildlife crime?

So long as we continue to consider wildlife crime as a separate, isolated offence, rather than treating it as the vast, interconnected and transnational crime that it is, there is only so much progress that can be made in countering it. It’s crucial that this crime be taken seriously, and not only because of the severe consequences for the ecosystems and human communities surrounding poaching sites. Wildlife crime holds major global risks for public health and security, as well as facilitating other crimes, such as bribery and corruption, money laundering, and drug trafficking. By seeing modern wildlife crime for what it is, we can take a more effective approach to countering it and, in turn, the crimes it is associated with.

Cross-industry collaboration

As wildlife crime networks are so interconnected and far-reaching, a cross-sector approach is needed to counter it effectively. Law enforcement, NGOs, financial institutions, travel companies and government agencies must work together and share information, and it’s important that we do not overlook the financial aspects of – and larger networks related to – these crimes. When we take adequate measures to counter wildlife crime, we also help tackle other forms of transnational organised crime, giving criminals nowhere to hide.

Combining data sources

Alongside combining approaches and industries, a large range of data sources must be used to reveal deeper insights about transnational criminal networks. Effective use of OSINT is key here, as it leverages publicly available data to draw connections which would not have otherwise been clear. For example, corporate records can reveal who is involved in the front companies concealing wildlife crime and social media, used heavily by organised crime gangs, can be used to unveil links between individuals and pinpoint where goods are entering the market.

You can learn more about wildlife trafficking by watching our webinar with United for Wildlife.

- TRAFFIC | Wildlife Crime

- World Wildlife Report (unodc.org)

- The real cost of wildlife crime – United for Wildlife

- Crime Convergence Report (wildlifejustice.org)

- Mexican cartels are increasingly moving into wildlife crime (nationalgeographic.com)

- To fight illegal wildlife trafficking through hot spots like Miami, follow the money – United for Wildlife

- Operational alert: Laundering the proceeds of crime from illegal wildlife trade (canada.ca)